One of my favorite book series as a kid was The Baby-Sitter’s Club. My friends and I read and re-read them. My favorite character was Stacey McGill, who among many other attributes, has type 1 diabetes. I credit me knowing and identifying the symptoms of diabetes in Hazel to reading these books. When I heard that Netflix had made a series based on the books, I knew I had to watch it. Last night, we started the series together. I loved how they kept so true to the books while updating the setting. The basic premise of the books/show is that four girls start a club to make it easier for parents to find baby-sitters. The four girls who are in the club are in seventh grade. My three kids loved it for different reasons.

I was curious how they would portray diabetes in the series. I haven’t finished all the episodes yet, but I can say that while not terrible it is not a perfect representation. I think it’s great to have a character with t1d, but there are some challenges to the way it’s portrayed. If you do not want spoilers, stop reading.

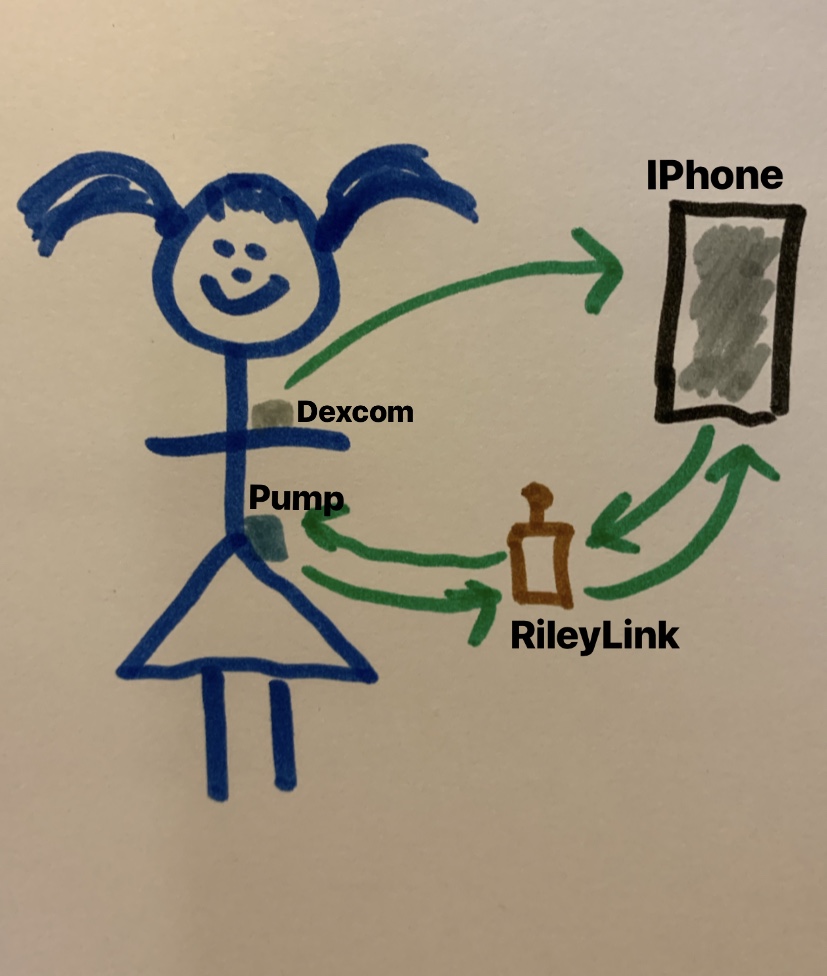

In the first two episodes, diabetes is not mentioned at all, but we see Stacey turning down snacks and eating a salad instead of pizza. Stacey has just recently moved to Stoneybrook, so the other girls who have all grown up together do not know her as well. The third episode is entitled “The Truth About Stacey,” just like the third book. In the beginning of the episode, we see Stacey trying on clothes with her mom. Her insulin pump (a Medtronic 670) is clipped to her side. The mom is trying to help her find clothes that keep it hidden. The mom seems like she is dealing with diabetes in a way that is harmful to Stacey. Throughout the episode we see Stacey treating lows, addressing the beeping pump, and feeling afraid that someone will find out about her diabetes.

In one scene, Stacey feels her blood sugar dropping while she is with her friends. She is afraid to treat it in front of them and leaves after saying things that don’t make sense. She walked home alone. When her mom came home and found her treating her low, the mom was freaked out and started making more doctor appointments.

The truth comes out after a video is spread around of Stacey having a seizure. It’s a poor resolution video, so not too graphic, but still hard for me to see–and troubling for me to wonder what Hazel thought. Stacey explains to her friends that she has type 1 diabetes and that video was taken the day she was diagnosed. She said that she had been losing weight and kept getting sicker until she went into “insulin shock” and had a seizure. This is problematic for two reasons. 1) “Insulin shock” is a non-medical term for having too much insulin in your system and blood glucose levels dropping too low. This usually happens when someone is taking synthetic insulin, not when their body stops producing it. 2) Hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) rarely causes seizures—it can happen, but seizures are much more common with low blood sugar.

After learning that Stacey had been cyber bullied because of her diabetes, her parents trying to help her hide it in a new town made more sense (and made them a bit more sympathetic). Still, they are far from the role model diabetes parents. The episode picked up a theme that ran deep through the book by the same title: Stacey’s parents were in denial. They were constantly making appointments with different doctors trying to find answers that did not result in their daughter having an incurable, difficult to manage disease. Seeing that struggle was probably the hardest for me. I remember in the first few months after Hazel’s diagnosis looking for anything that could give me hope that the disease was not permanent.

After the video of the seizure is sent out to all the parents of the kids the girls baby-sit for, the club members call a meeting and invite those parents. Stacey explains to the parents that she has type 1 diabetes and that the video was taken before she was diagnosed and she knows how to take care of herself now. The parents start asking questions like, “how do we know our kid is safe with you, couldn’t it happen again?” and “Do you have medical equipment with you that could hurt them?” Another parent, who happens to be a pediatric endocrinologist, defends Stacey and the conversation turns to how good the girls are as baby-sitters.

The episode ends with Stacey bedazzling her pump and wearing it with pride. Her mom makes it clear that she wasn’t ever ashamed of Stacey or her diabetes, but she just didn’t want her to be hurt again. In subsequent episodes you can see Stacey’s pump and she mentions diabetes care a couple of times, but it’s only a major plot point in the third episode.

One other slight diabetes related problem: there’s an off-handed comment made about Halle Berry having type 1 diabetes. Berry’s diabetes status is a bit contentious. You can read more about it here, but basically she does not need to take insulin which is not the case for people who have type 1 diabetes.

Overall, I am loving the series. I wish the writers would have consulted someone in the type 1 community to fact check so the diabetes details made more sense, but even with the problems they got quite a bit right. Hazel loved seeing a girl on screen with type 1 diabetes. Representation is power. In addition to diabetes, the series is tackling all sorts of hard problems and dealing with them well. I highly recommend it, especially for kids 8-12, with the caveat that episode 3 might be triggering for families that live with t1d. Pre-screening is a good idea.